We’d been talking about and putting off the “White Pine Removal Project” long enough that it earned an official name. It was clear for years that this was something we needed to do.

The six massive white pines around our lawn were encroaching on our house and leaning precariously out over our barn, covering everything in shade and needles – and pitch. Branches (the 4-inch-in-diameter kind) were constantly breaking off in the slightest breeze or lightest snow. Actual storms brought down much bigger pieces. But the cost and complexity of the project caused us to push it off, until last week. I wasn’t sure exactly what a tree care company would have charged to do the whole job, but it was clear that we couldn’t afford it. So instead it became a family project, with the help of my brother and some rented equipment.

Decades of growth had produced white pines that dwarfed, and leaned over, our house and barn.

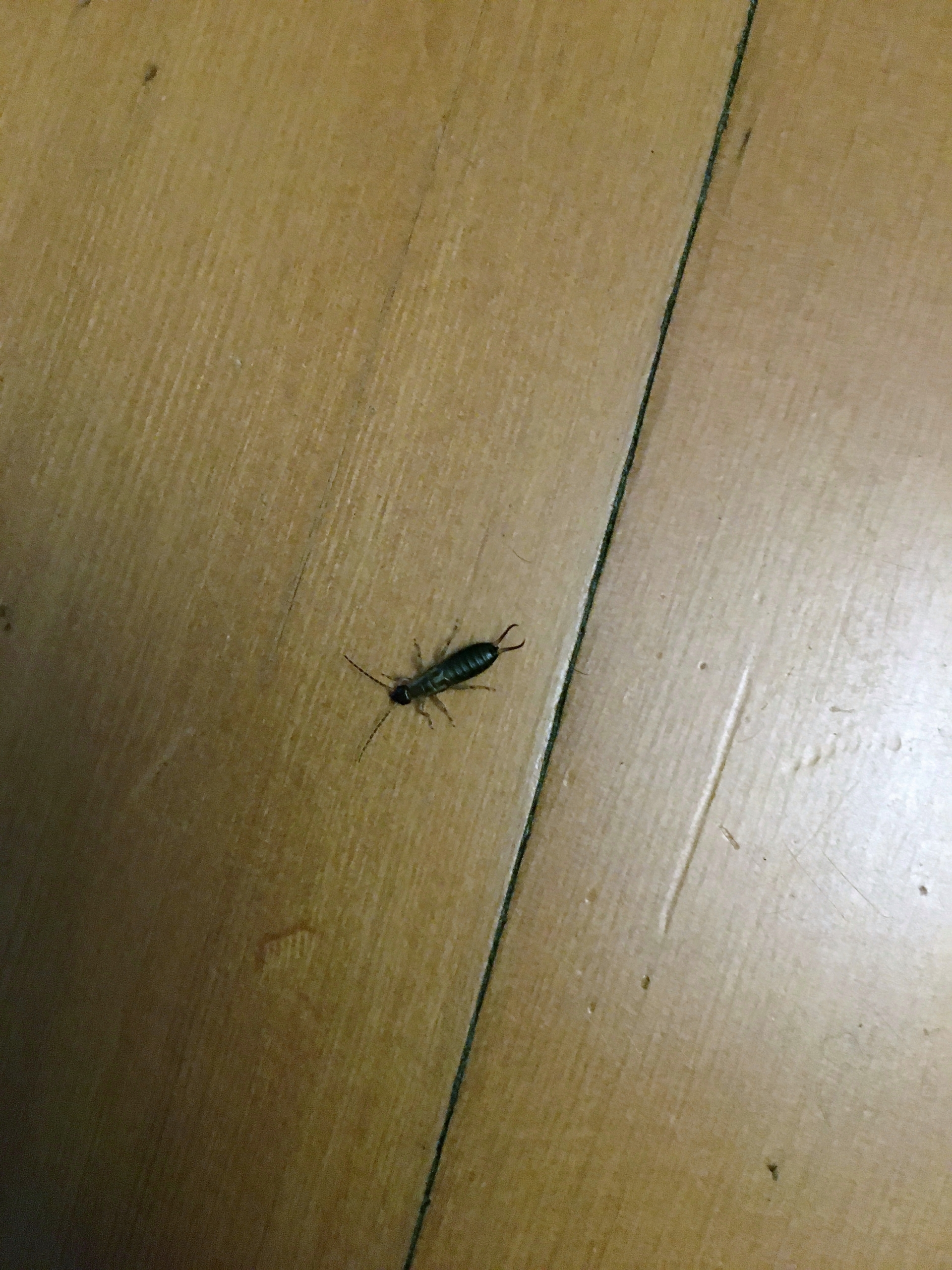

Day 1 began with the simplest of the removals – a 28-inch-diameter pine with a natural lean toward a relatively open area of the lawn. No fuss, no muss, no wedges. We had it on the ground in maybe three minutes. Then began the three-hour process of limbing it up and hauling away all the debris. Our white pines were not the forest-grown kind that European settlers marveled at when they first arrived on this continent –the towering, straight poles prized by the crown. No, ours were so-called “cabbage pines” that form when the trees grow in open areas with lots of sunlight. Each was probably 80 to 90 feet in height, but just as wide and with multiple stems starting 15 or 20 feet up the trunk. In that sense, each tree was really three or four trees. That means we had branches, branches and more branches to deal with. We started making piles in anticipation of renting a large chipper.

Mike White begins the bore cut on white pine #2. White pine #1 can be seen in the background.

The second pine came down nearly as quickly as the first. Wedges, and a 65cc Stihl with a 25-inch bar, helped us drop the 36-inch-diameter monster carefully between an apple tree and a maple. (Unfortunately, that meant landing it on my wife’s perennial garden.) Another several hours of limbing followed. Skipping over the branch-hauling for the moment, we moved on to the third pine. And that’s where our luck ran out. This one was the closest to our house. We hoped to wedge it in our chosen direction, safely away from the structure. But even with six or seven wedges pounded in place, the tree sat back and pinched the saw bar once the trigger wood was cut. An hour of pounding the wedges proved fruitless; they simply compressed the soft wood rather than lifting the tree and toppling it where we wanted it. Around that time, our rented 51-foot-tall man-lift arrived, so we used that to connect a climbing rope as high in the tree as we could reach and ran it to a come-along anchored to another white pine about 125 feet away. The four-ton come-along was able to put significant tension on the pull line, but simply wasn’t large enough to pull the tree over. So we returned to the lift and carefully, piece by piece, took off a major limb of the tree that was growing in the opposite direction. With the last of that counter-weight removed, the come-along was able to do its job and brought the rest of the tree down where we originally intended.

A rental lift let us prune back large limbs growing over the barn.

Day 2 started with sore muscles, and a shift to more precision work in the lift. Using an electric chainsaw and a 59cc Jonsered, both with 16-inch bars, we pruned back the large branches of the pine leaning out over our 200-year-old barn. We tied each section off to a remaining part of the branch so that the cut portion was left hanging from a carabiner; we then lowered each piece by hand with the help of a belay device. In this way, we protected the roof of the barn and those of us working on the ground. Piece by piece, that half of the tree slowly came down. We cleared everything that was hanging out over the barn, but eventually reached a point where the remaining stems were too tall for our lift to safely tackle. Fearing for our barn and our safety, we left the rest of that tree for someone with more expertise, and maybe a crane, to tackle. The remaining hours of daylight were spent with more limbing (using the Jonsered, a 59cc Husqvarna and a 30cc Echo) and brush hauling.

The beginnings of the pulp pile.

On the morning of Day 3 we began to finally cut up the large debranched trees that lay all around our lawn. Before beginning, I had called county forester Dan Singleton, who gave me the names of a few people who might be interested in the wood for pulp. We weren’t looking for any money, I told him, we just wanted to get rid of the wood and hoped there might be a better use than simply piling the logs in our woods. “The pulp market isn’t great right now, especially after the mill exploded in Maine,” he cautioned me. (This dashcam video with plenty of profanity shows the dramatic scene of the mid-April explosion at the Androscoggin Mill, where much of the pulp wood from our part of Vermont had been going.) But I called Tristan Vaughn at Grizzly Mountain Trucking in Groton, Vermont, who told me he would take a load. So we cut the logs to the specs he gave us: 26-inch diameter max down to about 5 or 6 inches, lengths of 8, 12, 16 or 20 feet. The open-grown pine was rarely straight enough to get 16-foot logs, so we focused mostly on 8’s, with 12’s when possible.

We dropped a couple more pines on Day 4, and began moving and stacking all the logs with a rented Cat 259D compact track loader equipped with a large grapple. The machine weighed about 9,000 pounds and could lift almost 3,000 pounds, yet unless a sharp turn was required did almost no damage to our lawn. In the 24 hours we had it, we got pretty quick at picking up the logs and and dropping them where we wanted them. The first log of each tree was often too large in diameter, so those had to be dumped in our woods. Likewise, logs too twisted to be loaded onto a log truck were also dumped, save for five or ten that I aside to burn in my outdoor boiler. But even after dumping at least five cords of wood, we ended up with a stack of about seven cords of pulp, and two saw logs (cut to 16 feet, 6 inches), for Tristan.

After the dust settled, there were seven cords of pulp and two saw logs ready for pick up.

The grapple also sped up the collection of branches. But the chipper we rented refused to start, so those piles will have to be chipped later. Eventually sensing we had piled all that could be chipped in a single day, we next started making a burn pile that quickly became enormous; someday this coming January you might be able to see the fire from space.

Day 5 was lawn (and perennial garden) clean-up; even after four days of work, there were plenty of small branches and needles left to take care of. All told, we spent about $1,200 on rental equipment and delivery. That’s only a fraction of what it would have cost us to hire the job done, as long as we don’t account for our time. Five long days is a lot of sweat equity, so whatever a tree care company might charge is well-deserved. And though we prioritized safety at every step, there’s undeniable danger in this kind of work. We’re fortunate that there were no injuries to people or damage to buildings, and we have some stories to tell.

Mark Isselhardt, UVM Extension

Mark Isselhardt, UVM Extension