Dispatch from the Sugarwoods, 2021, Part I

Because it’s so intensely seasonal and labor intensive, sugarmaking has always been something of an economic side-gig. In the vertically-integrated family-farm days, maple was the first crop of the year, the literal seed money for the seed that went into the ground in May. No one was just a sugarmaker, because collecting buckets is so labor intensive that it kept operations small. The old axiom was that one adult could run 500 buckets, which is to say hang them, collect them, boil that amount of sap.

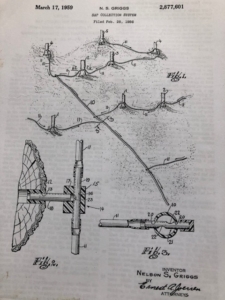

This all started to change in the mid twentieth century with the advent of maple tubing that allowed sap to just run down hill into one collection tank. But the revolution didn’t happen overnight. The image here shows a patent for early plastic tubing, filed in 1956.

A modern producer would look at this setup with tubing running along the contours of the ground and think ugh, imagining mold, squirrel and mouse chews, ice blockages. Tubing systems and installation techniques improved rapidly, but even in the 1980s, when I was a boy, rudimentary soft plastic tubing drooped from tree to tree.

Today things are very different, and people around the state are hell bent on proving that sugaring can be an occupation in its own right. Modern producers use semi-rigid, food-grade plastic that’s designed to be pliable enough to work with but rigid enough to hold a straight line downhill. We have fittings that allow proper tensioning, and vacuum systems that woosh the sap downhill to the tank. Reverse osmosis machines can turn 1,000 gallons of sap into a 100 gallons of concentrate with the push of a button. In theory, with the proper setup, one adult can run thousands of taps. Rumor has it there’s an operation somewhere in northern Vermont where one guy’s running 10,000 taps by himself.

But for most people, this isn’t going to work. Technological promise is one thing, technological execution is another. Pretending you can buy enough gadgets to allow you to run 10,000 taps alone is like pretending you can seamlessly transition from in-person to remote learning in a school with enough Microsoft and Apple products. It sounds good on a slick video, but on the ground there are endemic roadblocks that technology just can’t solve, like the fact that a lot of people in Vermont still can’t get high-speed internet (he writes bitterly while staring at the blinking modem on his pathetic wireless system).

I’m thinking about the how-many-taps-can-a-person-run-alone question because that’s what I’m up against this year. The extended family chips in every sugaring season, but the main drivers are my father and I, and Dad’s laid up with a bum leg. I’ve started tapping our 3,500 trees, but I’m trying hard to keep my expectations realistic as to what comes next.

The big roadblock thus far has been deep snow – knee deep in one bush, between knee-and-thigh deep in the other. The hovercrafts that might eventually glide us from tree to tree have yet to be invented, so I’m stuck with snowshoes, grit, and help from dear friends and family. Four other adults and two teenagers helped out last weekend, and we’re about 60 percent in. The weather will be conducive for sap later this week, so I’m off to keep up the battle. I’ll aim to post dispatches regularly every Monday for the rest of the season.